Image: Ashley Landis, The Associated Press/Rare Design Group

Statues of Limitations

The Changing Nature of Cultural Symbols

By Keith Hamilton

Change is unsettling. I’m reminded of this every time our practice presents a logo concept; there is an existential queasiness associated with changing the visual identity of a business or organization. Sometimes it’s experienced by the immediate client, even if they’re fully expecting it, but more often I see it when it’s shared with board members or even their public, who are not. Human nature bends toward familiarity like flora to the sun.

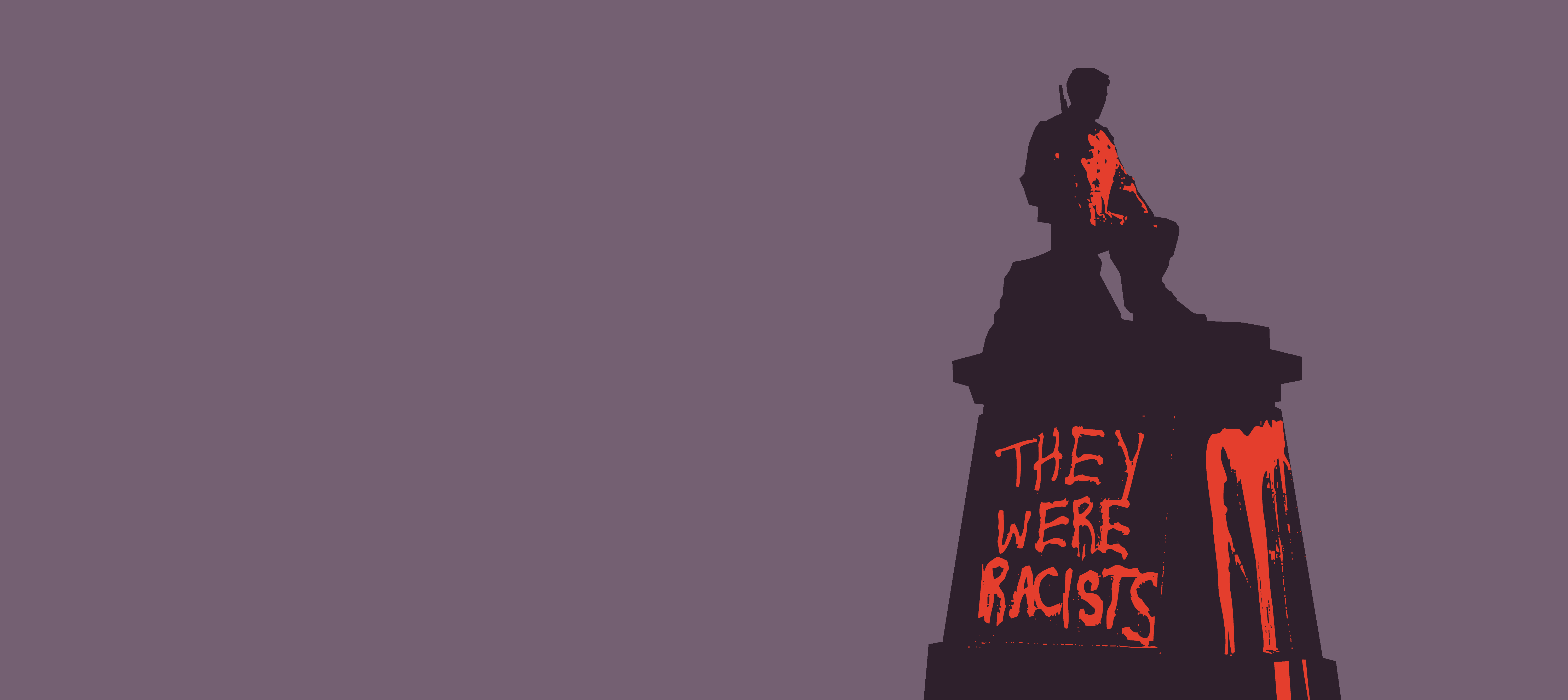

Culturally and societally, change is upon us. Leveraged by social media and in reaction to indifferent and hostile world orders and world leaders, voices supporting #metoo and Black Lives Matter have demanded a reckoning. What we used to embrace as the status quo is now called under re-appraisal, including the symbols that dot our cultural and mental landscapes.

Brands and corporations have responded in kind, strategically disassociating their brand identities, their logos, from the anything that appears racist, sexist, or homophobic. NASCAR, a bastion of the white midwest, made a potentially polarizing move by banning the Confederate flag, echoing Nike’s stated allegiance with former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick when he took a knee against police violence. While morally justified, both brands risked alienating their markets. Good corporate citizenship no longer sits on the fence.

Governing policy is another matter. On one hand, the current US Administration’s avowed protection of ‘heritage’ symbols is just as random as any recent messaging from the White House. There is, of course, more tied to the initiative — distraction tactics and re-election gambits — but regardless of nation or culture, statues are monuments, literally, to a person or persons and their associated achievements. If these include fighting (and even losing) a war against human rights, then really the question is how they got there in the first place. These are not symbols of objective history, but of a one-sided history written with a racist throughline.

The symbols we prop up are reflective of the values we profess.

But one of the problems with systemic racism is that it can be hard to identify traditions as racist when they are deeply ingrained in our social constructs. We may not stop to think about the history of a general on horseback (slave owner) or an airport named after a Hollywood legend (avowed white supremicist); but in fact, it’s necessary, since monuments to racism remind us of a history of oppression that many have not entirely escaped — socially and economically — and as such hasn’t ever really gone away.

We cannot claim ignorance as an excuse for retaining the symbols that are reminders of an oppressive past, however unintentional. Just like a logo that inadvertently ‘borrows’ from another, it may take research and education so we know what we’re advocating, even advocacy that is manifested by our silence. We need to understand the symbols around us, because those that we prop up are reflective of the values we profess.

In an online stunt, the once-innocuous hand gesture commonly known as the ‘ok’ symbol was appropriated by the far right, and by probably any rational person’s perspective, they can have it. Being unaware of this subversion is its only power, effective only when oblivious non-racists either use it or they see it used and fail to condemn it. With awareness, it can go the way of the swastika which went for centuries representing prosperity and good luck before it was hijacked by a similar movement.

Even more, we have to be aware of symbols that never even started out that way. In the midst of a global pandemic, the president uses his personal choice to be seen without a face mask as a symbolic gesture. He will not give his political enemies the satisfaction of his perceived acquiescence to a disease he insists his administration is defeating, despite evidence to the contrary. Unfortunately, this sets a precedent that many will follow, if only out of principle — a means of suppressing an infectious disease becomes political. Again, most rational people would suggest a face mask is just a face mask. But, practicality aside, if it is elevated in our collective consciousness into something greater than itself, the question remains if it is symbolic of saving lives, and even the restoration of the economy, or if it represents the un-American limitations of personal freedoms. As cases increase and deaths accumulate, the world will have its answer after polls close in November.