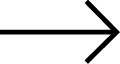

Image: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Rare Design Group; Photo: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

The Disquiet of Basquiat

An Artist’s Prelude to Black Lives Matter

By Keith Hamilton

As a white Canadian kid growing up in the 80s, I was held in thrall by the kinetic energy of the post-punk New York art scene. Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, Barbara Kruger, Talking Heads, Run-DMC. Intuitively I gravitated towards art that was commercially viable, direct, and street-level — graffiti-inspired, efficient, you’re in and you’re out and nobody gets caught.

Among his peers, Jean-Michel Basquiat captured this urgency better than anyone. If Haring was graphic accessibility, Basquiat was layered rage. Any rules that governed art were of his own making. He saw his visceral, oil stick and ink drawings equal in stature to his painted works rather than a means to their end. In contrast to Warhol’s methodic screen prints, his compositions threatened to careen off the canvas.

Now, with his 1982 work Untitled (Head) having netted over US$13 million, we’re called once more to reconcile this rage, and, bluntly, the 2020 cultural landscape hasn’t evolved much. Social justice in the context of race was always present in Basquiat’s works, barely hidden beneath his jagged shards of blues and reds. In 1983 he created The Death of Michael Stewart to acknowledge the fate of a young, Black artist killed by New York City’s transit police after allegedly tagging an East Village subway station. In 2019, an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City was devoted to this specific event and American racial oppression in general. His works were contextually supported by those of Warhol, Haring, and George Condo, all white men, meant to underscore the solidarity he found among his peers. Among these men, it was implicit that Black lives mattered.

If Haring was graphic accessibility, Basquiat was layered rage.

What neither this work nor its exhibition directly portray is a prevalent brand of oppression against Black people that is no less violent but equally dehumanizing. In an appalling case of life imitating art, the Guggenheim show itself was riddled with controversy for the treatment leveled to Chaédria LaBouvier, the first Black curator and the first black woman to curate one of its exhibitions. In response to claims that her curation was undermined and second-guessed, a representative from the Guggenheim refuted LaBouvier’s allegations, claiming the process was a fully collaborative one. LaBouvier responded that the harmful treatment she received while working for the museum was compounded by repeated denials of her own experience. It could be this defense is disingenuous, or it could just as easily be that a predominantly white administration truly believed it did no wrong.

The details of this episode may of course never come to light. The fact is microaggression — as well as overt aggression — is directed toward Black people all the time, and that’s something that’s only beginning to sink in among those who have always silently benefited from the existing power structure. As one Minneapolis teen protesting the George Floyd murder explained, “it’s not just about George Floyd. It’s about all the unseen shit, where we don’t have the video.”

Equally unknown is the depth to which the cross-racial solidarity extended among the artists in Basquiat’s orbit. The naive kid forty years ago would have wanted to think it was a high-art version of the mixed-race buddy cop movie, or, years before its namesake was outed as a predator, The Cosby Show as it ostensibly shared the same mythologized values as Family Ties. It was Springsteen and Clemons, Ali and Cossell. Human relationships are complex; probably it was and it wasn’t. Regardless, the focus now is how to move forward and support Black artists, businesspeople, activists — everyone — if we’re going to get anywhere as a single race. Because while as a society we’re fortunate to be reminded of Basquiat’s genius, it’s a tragic indictment of our present society that we must also acknowledge his enduring relevance.